For those of you who know me outside of this blog/newsletter, you’re likely already familiar with my passion and background in studio art, art history and art education. Since 2016, I have been committed to a pragmatic application of art history, theory and methodology within a K-12 school curriculum. I started a blog and digital learning platform called Artfully Learning to share my insights on art theory, history and contemporary art practices in a manner that might be beneficial to educators and students. My focus is integrating art history across the entire curriculum, which means making connections between art and other subjects like math, science, language and physical education.

On Artfully Exercising I am interested in describing the ways art has referenced physical fitness, and our personal and cultural insights regarding exercise. Since art is a discipline that reflects the way cultures value physical forms, it often communicates aesthetic and corporeal concepts of body image. Art’s role in shaping and reinforcing cultural clichés about gender, beauty and health is pretty clear. Just close your eyes and think about what necessitates the perfect physique based upon the prior imagery of bodies you have seen in art and media. The rock solid muscles of Michelangelo's David and John Singer Sargent's sensual, soft and provocative painting Madame X, are archetypal examples of what is considered to be the ideal masculine and feminine body images.

Just as art has established certain standards over the course of its long history, it has also been at the forefront of powerfully rejecting and diverting the status quo of body image. The absolute truth is that everyone should be respected for their own bodies. We each should have the agency to express our physical identity without fear and the vitriol from bullies, ableists and bigots. A greater understanding about the importance of intersectional body positivity can be achieved through art and visual media education.

Another way that intersectional awareness of body identity is strengthened is through physical education. Physical education (PE) might be one of the more misunderstood disciplines in a school's curricula. Gym class and PE teachers are often negatively portrayed across popular media outlets. Far from the drill sergeants and body shaming bullies, physical educators provide a differentiated instruction that promotes body positivity, awareness and diversity.

The arts and PE might seem to be at odds within the curricula, but there are many examples of how they are interlocked. Claude Cahun, Cassils, Shaun Leonardo and Augustas Serapinas are examples of modern and contemporary artists who combine the practices of art and exercise to present empowering and provocative portrayals of identity.

Claude Cahun

Ahead of their time in many ways, Cahun was a French Surrealist and a multidisciplinary artist, who is also a cultural icon for their gender nonconforming art and persona. Around 1930, they said that “neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” Cahun’s work expresses the multifaceted and layered nature of gender identity, by depicting themselves in self-portraits where they performed as both male and female. These expressive compositions challenged the idea of a gender binary.

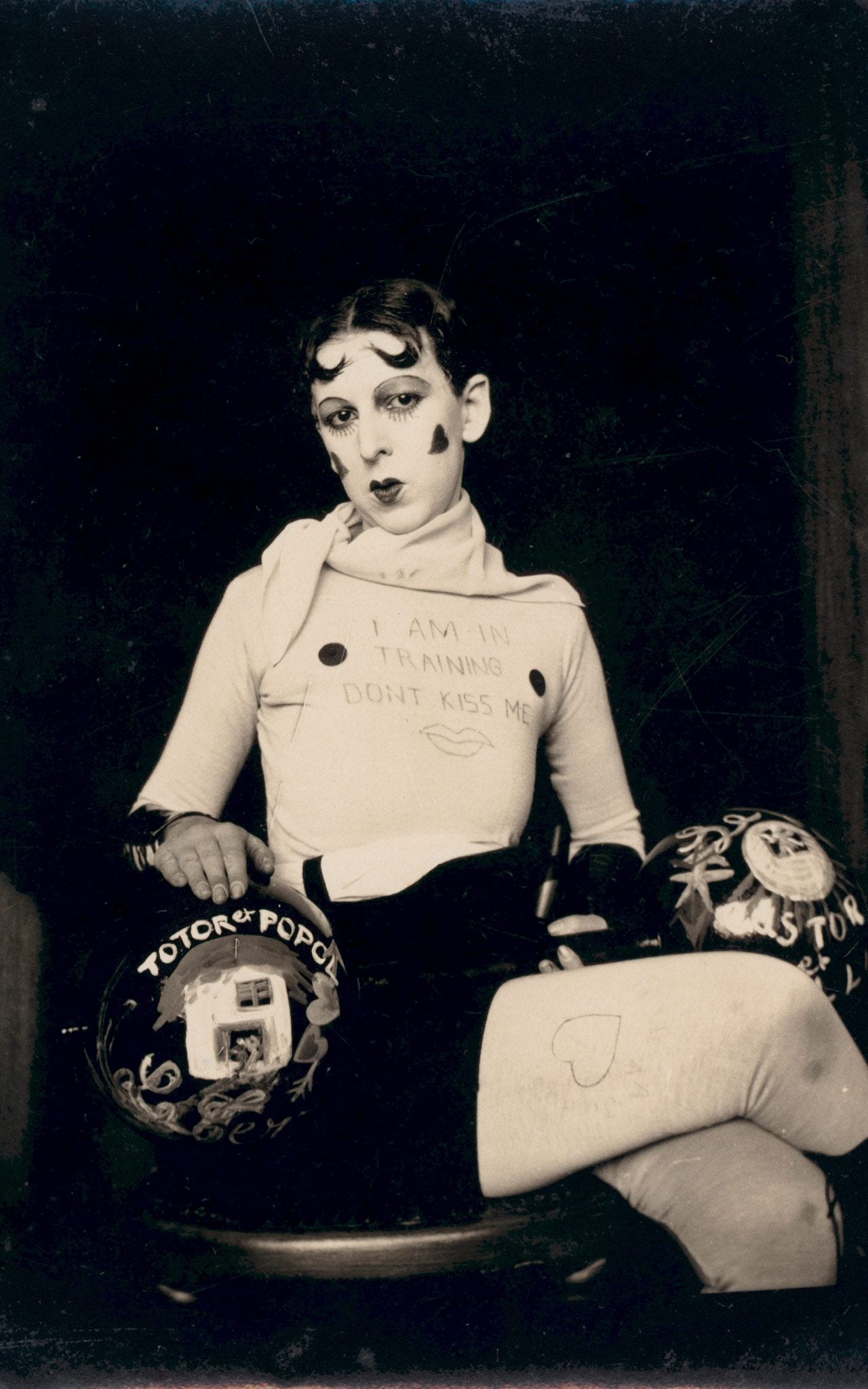

In a 1927’s Self-Portrait (as weight trainer), Cahun claps back at the role of the male gaze and gender hegemony in both the art and fitness cultures. They have created a persona that mimics the aesthetics of masculine, heterosexual perspectives by obfuscating and contradicting traditional gender roles and idealizations of male and female body types.

Poised and posed, they sit cross legged donned in a nude bodysuit with dark boxer shorts on top. Their hair is parted into symmetrical curls, and their expressive application of makeup boldly draws our attention to their assertiveness and whimsy. It is a replete combination of beauty, intellect and brawn. They eschew and rebuke the male gaze with the words, "I am in training don’t kiss me,” painted across their leotard.

Across her lap sits a sculptural barbell with names of fictional and mythological duos: Totor and Popol and Castor and Pollux. Totor and Popol are characters from Belgian cartoonist Hergé’s oeuvre (he is also the creator of the well known Tintin comic strip). In Greek and Roman mythology, Castor and Pollux are twins also known as the Dioscuri, or in Latin, the Gemini. They had the same mother, Leda, but Pollux, was born to a god and was immortal, while his brother was born to a human and was thereby mortal. Pollux asked Zeus to let him share his own immortality with his twin. In order to keep them together, they were transformed into the constellation Gemini. It is assumed that these two sets of pairs signify Cahun’s own multiplicity of identity, and are also perhaps an homage to the bond and collaborative relationship they had with fellow artist and gender nonconformist, Marcel Moore.

Self-Portrait (as weight trainer) poignantly reflects the treatment of women in sports. While muscles are associated with athleticism, women athletes can be ridiculed if they are perceived as “too muscular.” Black women and trans women athletes face extreme forms of bias related to their physique and body identity and are often inequitably compared to their male counterparts. This unjustly negates what they have accomplished in their sport, and is shattering to all individuals who are told they are different, “abnormal” or less-than someone else because of their physical body type.

The aforementioned bias applies to all body types that are not within the range of the status quo for an “ideal” masculine or feminine body. The notion of what is desirable, fit and healthy has been perpetuated throughout popular culture and has been associated with leisure and success. Art critic Daniel Kunitz (2017) states that: “Today, the cost of access to the highest-quality food and gyms, as well as to the best information about how both ought to be used, has spiked. As a result, privilege is signified by figures with low body-fat percentages that showcase taught muscles, by the leisure to afford long workouts in expensive gyms, by eating regimens crafted by coaches and trainers, by tans that bespeak travel, and by fitted, expensive clothing that accentuates these advantages.”

Cassils

While Cahun performed the role of a weight trainer, contemporary artist Cassils is an actual bodybuilder and personal trainer. They utilize their physique and their skills and knowledge of fitness as an artistic medium, as well as a subject for mediating performativity (how “identity is embodied and enacted, rather than a more or less adequate reflection of some underlying bodily reality.” see: McKinlay, 2010 and Fraker, 2018). Through a creative process that includes athletic and weight training, nutrition, photography, video, sound and sculpture, Cassils highlights the visibility of the transgender body. Art historian, David J. Getsy (2018) elaborates: “In some performances and photographs, Cassils has defiantly exposed their body, knowing this will solicit viewers’ intrusive gazes and suffering the voyeuristic objectification that many viewers unquestionably perform. The artist does this to short-circuit the lurid, diagnostic fascination that has historically shadowed the visibility of the transgender body. Cassils’s work incites voyeurism to subvert it.”

Cassils’ photographic series Alchemic, reinterprets iconic photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s nude photographs of male figures in classical poses, which he often cropped in a manner that highlighted and abstracted the physical forms of his subjects. In the 1980s, Mapplethorpe’s imagery was revelatory for its subversion of masculine tropes in visual culture. Through his work, Mapplethorpe challenged the heteronormative gaze of both male and female bodies. As his friend, poet and musician Patti Smith contends in her 2010 memoir, Just Kids: “He worked without apology, investing the homosexual with grandeur, masculinity and enviable nobility. Without affectation, he created a presence that was wholly male without sacrificing feminine grace. He was not looking to make a political statement or an announcement of his evolving sexual persuasion. He was presenting something new, something not seen or explored as he saw and explored it. Robert sought to elevate aspects of male experience, to imbue homosexuality with mysticism.”

Cassils’ response relays significant messages about how not all bodies are valued within the collective culture. Trans bodies in particular have been subjected to harmful stereotypes, which other them outside of both traditional body norms and heteronormative gazes. Mocking the predominant scope of traditional body and gender idealizations, Cassils’ paints her figure in gold, turning the human being into a trophy. Recognizing that no two bodies or experiences of identity are alike, Cassils avoids being blatant in both narrative and imagery, and “offer works that attempt to open up the complexity of trans experience while calling for visceral identification and political reflection from all viewers” (Getsy, 2018).

Shaun Leonardo

Leonardo’s performance artwork critically addresses and dismantles traditional notions of gender and race. An overarching theme in his art is a grappling with the idea of manhood. He scrutinizes popular ideas of hyper-masculinity and how stereotypical cultural obsessions with idealized male identities affect the social, emotional and cognitive development of men. Subjects that inspire his performances include professional sports and comic book superheros.

Leonardo, himself a former football player, relives the arduous experiences of performing hyper-masculinity, while also addressing how these stereotypes impact Black and brown bodies. This is exemplified in his physically exhaustive performances like El Conquistador vs The Invisible Man (2006) and Bull in the Ring (2008).

El Conquistador vs The Invisible Man takes its name from a character Leonardo created of a Luchador (an oft-masked professional wrestler) and Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel, Invisible Man. In the performance, Leonardo wears a Mexican wrestling mask and fights an invisible opponent. Paying homage to Ellison’s novel, the artwork is a metaphor for how race and identity affect ideals of gender and body image. In the novel, the narrator, living in a small Southern town, is awarded a scholarship to an all-black college. However, he must first endure a gauntlet of fights, performed for the entertainment of the town’s affluent white hegemony. In both Ellison and Leonardo’s works of art, a person of color must exert their bodies for spectacle, placing an emphasis on how society stereotypes their physique as a combination of brute strength and aggression.

Leonardo performed Bull in the Ring with a cast of ten semi-professional football players. The artwork’s title comes from a training routine that is banned from high-school and collegiate levels of American football. The activity symbolizes the way a matador toys and taunts a bull. One player is positioned within the center of the field, surrounded by a circle of their teammates. They assume the role of the matador. The coach selects from their teammates at random, one player to charge at them, which often results in the player at the center being caught off-guard and taken down. The concept behind Leonardo’s enactment of this brutal game, is to represent the pressures that men face in having to prove their masculinity.

Augustas Serapinas

Upon seeing footage of Augustas Serapinas’ Čiurlionis Gym (2023) on a friend from the artworld’s social media timeline, I felt a kindred connection to the young Lithuanian artist. Coming into my passion and dedication to fitness and personal training from an arts background, it helps give me perspective when I see others who combine the two disciplines.

Serapinas is clearly a dedicated artist and a fitness enthusiast. The case in point is his installation of sculptural fitness equipment that merges the aesthetics and functionality of a high class gym and art gallery. The initial installation of Čiurlionis Gym took place at this year’s Art Basel, which adds to the performative and exhibitionist concepts behind the work of art, and highlights the focus on aesthetics and rigor in both art and fitness communities.

Researching the work further, I was elated to learn that there is also an educational component. Čiurlionis Gym was influenced by Serapinas’ experiences as a student at the National M.K. Čiurlionis School of Art in Lithuania (named after one of Lithuania’s best known modern artists, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis). The school employs a very traditional pedagogical framework focused on building technical skills in the plastic arts (i.e. drawing, painting and sculpture) by having students copy what they see in nature, and making recreations of classical artworks, such as ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. The plaster replicas of classical sculpture he made in art school are incorporated into the design of the fitness equipment in Čiurlionis Gym.

Reflecting on the labor intensive nature of making art and working out, Čiurlionis Gym prompts us to consider, and perhaps reconsider, our ideals for education, art and physical training methods that are based on a mimicry of classical forms and actions. These standards typically ignore the fact that we each embody distinct physical, cultural and intellectual identities that are best addressed on a basis that is best for our overall well-being.

Being active is not always indicative of a “gym body.” As we know from the field of education, not everyone learns the same way, therefore lesson plans need to be differentiated and flexible in order to teach to the whole student. The same goes for physical activity. Planning a fitness routine is not a one-size-fits-all scenario. This is true because everyone’s bodies and overall wellness goals and needs are unique. While working out will certainly provide physical results; the arts can be just as transformative in terms of building strong personal and collective perceptions of body positivity and wellness.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Fraker, Will. “Gender is dead, long live gender: just what is ‘performativity’?” Aeon, 24 January 2018. https://aeon.co/ideas/gender-is-dead-long-live-gender-just-what-is-performativity

Kunitz, Daniel. “How Art Has Depicted the Ideal Male Body throughout History,” Artsy, 5 April 2017. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-art-depicted-ideal-male-body-history

McKinlay, Alan. “Performativity and the Politics of Identity: Putting Butler to Work”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, vol. 21, no. 3, March 2010. pp. 232-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2008.01.011