Chiseled: The Relationship Between Abs, Bodybuilder Aesthetics and Art

If you are not yet ready to become a paid subscriber, you can support my work with a one time pledge (monetary value of your choice) of support:

I recently read a fascinating piece written by Conor Heffernan, a scholar of Physical Culture and Sport Studies at The University of Texas at Austin's College of Liberal Arts, about the history behind the “six pack” obsession. The article references a neoclassicism zeitgeist throughout European culture, as an impetus for developing chiseled abdominal muscles. Art and art history had a major role in spurring this trend onward.

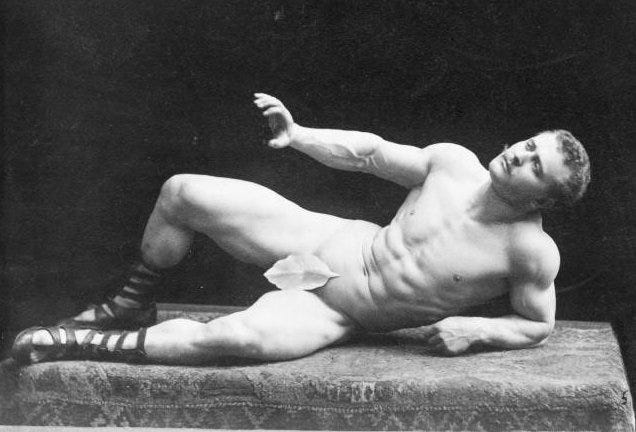

In the late nineteenth century, bodybuilders revisited the physical attributes of ancient Greek and Roman artwork (which notably had robust abdominal muscles), in order to devise the “Grecian Ideal" as a formula for obtaining the "perfect physique.” Eugen Sandow, the most renowned bodybuilder of this era, actually measured the statues in museums, and sculpted his own body to meet the exact proportions of these works of art. Because of Sandow’s methodology, bodybuilding became a practice of precise physical and aesthetic measurements.

Sandow’s muscular frame was all the rage throughout popular culture. Audiences were more captivated by his posing and flexing than actually seeing him working out. Therefore, he focused on "muscle display performances" rather than feats of strength. This was a widely successful endeavor, and can certainly be considered as a precursor to today’s Mr. and Ms. Olympia competition.

In order to truly embody the Greco-Roman spirit and the artistic concept of heroic nudity, Sandow would often place a fig leaf over his genitals when he was being photographed for magazines. He was also the first bodybuilder to be featured in film, the newest art form of the era. Thomas Edison’s Sandow (1894) is significant for capturing the essence of Sandow’s "muscle display performances" in real-time.

While Sandow and subsequent bodybuilders like Charles Atlas (see: “The Fitness Influencer who was a Muse for Artists”) were inspired to mold their bodies like classical sculptures; contemporary visual artist and bodybuilder, Cassils (see: “Training the Mind, Body and Soul”), presents neoclassicism as a way to focus on gender non-conforming and transgender identities.

In their performance Tiresias (2021), Cassils melted a neoclassical Greek male ice sculpture using their body heat over a five hour period. The title of the performance references Tiresias, known as the blind prophet of ancient Thebes, who was transformed from a man into a woman for seven years. Cassils explains that, “By pressing my body against the ice torso, I demonstrate both the instability of the body and desire for a certain unsustainable physique…Recasting the myth of Tiresias as a story of endurance and transformation, I perform the resolve required to persist at the point of contact between masculine and feminine.”

Drawing inspiration from Sandow, Atlas and Cassils, I am revisiting my prior artistic practice through performative fitness. My body is raw art material, used in expressive ways to conduct repetitive feats of strength and endurance.

Exercise has two opposing outcomes for me, each with equal importance. It is a way of portraying my physical and emotional vigor, while also grappling with my mental health struggles. The dynamism of resistance training, and the willpower to progressively build upon an intense regimen of challenging workouts, is indicative of the push and pull nature of living with OCD. Above all else, I have proven to myself that my body can endure (and benefit from) significant stress and tension, and that my mind can be disciplined and focused on building physical strength and fortitude. This is a major step in my battle with OCD.

As I build upon my physical fitness training, I add my own flair and creativity to my workouts. I consider what I do now in my physical training to be akin to what I did when I was making art in my studio. I find the fundamentals of each discipline to be similar in terms of learning the trades by studying the work and theories of others (i.e. art theory and exercise science), and then inserting my own signature style into it.

I am also exploring ways of combining physical training with traditional and performative art media. Like Yves Klein’s painterly process of using human bodies as art materials, which he called “anthropometry,” I will use my body in the gestural act of exercise as a "living brush," to create marks on a surface. I also conceive and present my work as “living sculpture,” a term that comes from contemporary artists Gilbert and George, who covered their faces in bronze paint (to transform into sculptures), and walked around the streets of London as they danced and performed a repetitive series of actions.

Repetition and flexibility are the crux of many exercise routines. Both art and exercise are about aesthetics, process and self expression. There are elements of the process that I can control (i.e. my form, the specific type of workout routine and number of reps performed), but there are also unforeseen and random things that occur during a session. My background in art education has helped me to embrace spontaneity and ambiguity, in order to find inspiration and new insightful ideas within my tried and true methods.

I look forward to experimenting more with fitness as an artistic medium, and sharing the process with you all in future Artfully Exercising posts!

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Heffernan, Conor, “When men started to obsess over six-packs,” The Conversation, 23 February 2021. https://theconversation.com/when-men-started-to-obsess-over-six-packs-154128

I’ve been feeling that jogging and yoga can both be more similar to dance and artistic expression than usually assumed. Paying attention to form and grace more than anything these days. Partly due to your inspiration.